I’ve gone on tangents about nostalgia in previous reviews, and I often lament, like the old man I’m becoming, over how much ‘better’ life was in my pre-9/11 geek world. I gotta say, Stand By Me makes me feel guilty. As much as I loved my carefree Nintendo junkie existence, the movie makes me feel like I should have been outside experiencing coming-of-age kid adventures instead of obsessing over Dr. Wily’s robot dragon.

Oh, I doubt we would have played chicken with trains and logging trucks, or ventured through swamps infested with wiener-biting leeches. It wasn’t that kind of neighborhood, nor would Stand By Me have been a perfect depiction of my childhood even if I wasn’t socially retarded. This is writer Stephen King and director Rob Reiner’s nostalgia, not mine. Our songs would have been by Ace of Base, not The Monotones.

Regardless, there’s one thing kids and adults alike can pick up from Stand By Me no matter what generation they’re from: that prevalent, timeless loss of innocence. That happens to everyone in some way or another, whether it’s virginity loss, incarceration, a lost pet, or in this case, a dead body.

Stand By Me is a movie about four boys flocking together at a crucial moment in their lives, right before they will be forced to give up childhood and start becoming men. On a larger scale the movie is set in the summer of 1959, on the threshold of a war that will tear the nation asunder. For now there are no violent American massacres, no countercultures, and no corruption, not that we could see anyway. The powers-that-be are our best friends.

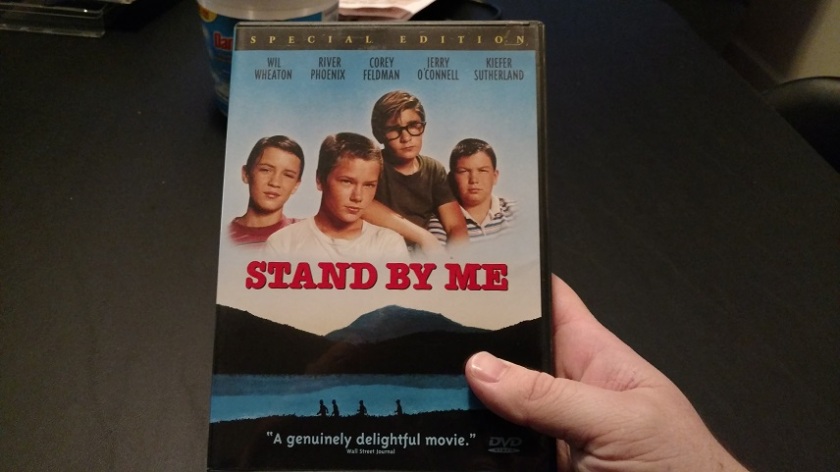

1959 in Stand By Me has all the big band music but none of the purported innocence. Chris Chambers (River Phoenix) is a street smart bad boy with the reputation for being a future troublemaker. Teddy Duchamp (Corey Feldman) is the “crazy” one, an impulsive adrenaline junkie with a history of horrific child abuse; his daddy crisped his ear on a hot stove before being hauled off to the loony bin. Young Gordie (Wil Wheaton), who narrates the story as an adult (Richard Dreyfuss) is the normal everyman, though the shadows looming over him are dark and foreboding.

The boys are smoking, cursing, playing cards and telling dirty jokes in their treehouse when Vern Tessio (Jerry O’Connell) the group’s fat mothermouth wimp, breaks the mundane summer day with an amazing revelation: a local kid who’s been missing for days has turned up dead, and Vern has overheard from his thuggish older brother Eyeball (Casey Siemaszko) where the body is. The kids immediately assemble into action, as claiming the corpse means prestige and possibly a cash reward. But moreover is the simple thrill of being twelve years old and going to look at a dead body. Anyone who was ever that age should understand the appeal.

Road trip movies are never about what lies at the end but what happens along the way. The journey doubles as sorely needed group therapy. It turns out that all of the boys are dealing with trauma. Gordie is haunted by grief over losing his superstar brother Denny (John Cusack) who recently died in a car accident. At home his parents are in perpetual catatonic states. They literally ignore Gordie, disregarding his existence as they wander about like zombies. We learn through flashbacks that they treated the younger son like a pariah even when Denny was alive.

Chris deals with the fact that his entire family has been stigmatized as the local trouble, from his drunkard dad to his bad older brother (Bradley Gregg) and beyond. The town already assumes he is destined to carry on the legacy and thus he is treated like a criminal, especially after he supposedly steals class money. The truth behind the real story, and the twist, is heartbreaking.

Teddy is the most dynamic and haphazard of the lot. The ear story is clearly no lie, and one would assume Teddy hates his papa for it. Instead it’s the opposite. Teddy not only worships his father for landing in Normandy, he aspires to join the Army as soon as he is able. Maybe it’s a defense mechanism, or something deeper and more complex. Teddy’s tendency to fly into rages and put himself in mortal danger could be construed as PTSD.

Vern seems to have it the easiest, though he lives in fear of his older brother. His cowardice may be his worst enemy. But all the boys have an enemy in Ace Merill (Kiefer Sutherland) the leader of the local delinquent gang. The kids may be mischievous, but Ace is a manipulative and vicious sociopath. Lives and personal property mean nothing to him, and when he catches wind of the body, our heroes may be in true danger.

Stand By Me isn’t about the glory the boys will gain by finding the body, or how the journey will make them best friends forever. It’s about how much they need each other at this moment in time. The body is of course a metaphor and a means to an end. The dead boy is where everything will come to a head.

That said, as much as I connected with and related to these kids, the script gets confused over how smart and clever they are supposed to be. I have a problem with movies where children are written as little adults instead of children. One minute the boys are chortling over “mama” jokes and the next they’re articulating like educated grown-ups. There are other places where the issue transcends into violating the “show, don’t tell” principle. We can pick up what the kids are going through by listening to and observing them, but then there are scenes where they flat-out explain what’s bothering them. I wish the writing had presented this in a subtler fashion.

It’s weird when kids talk like this in movies because real life kids don’t. When I was 12 I don’t recall anyone lamenting over their futures like college freshmen deciding on their majors. It was pretty much like the scenes where the kids are allowed to be kids: talking about tits and blueberry vomit while expressing occasional insight.

Stand By Me has great characters, a good human interest story and a sometimes questionable script. What it sets out to do it does well, which is to remind us that before adulthood slapped us in the face, we were all young and too curious for our own good.

Too relatable to go anywhere for now.

FINAL GRADE: B